A defining question of our time: How do we overcome loud misunderstanding?

I attended a virtual town hall event for Massachusetts’ Ballot Question 4 (Legalization and Regulation of Psychedelic Substances) last fall, emphatically nodding along to everything that was covered, and naively believing — like I did about a few other things in this most recent election cycle — that the majority of people would also agree.

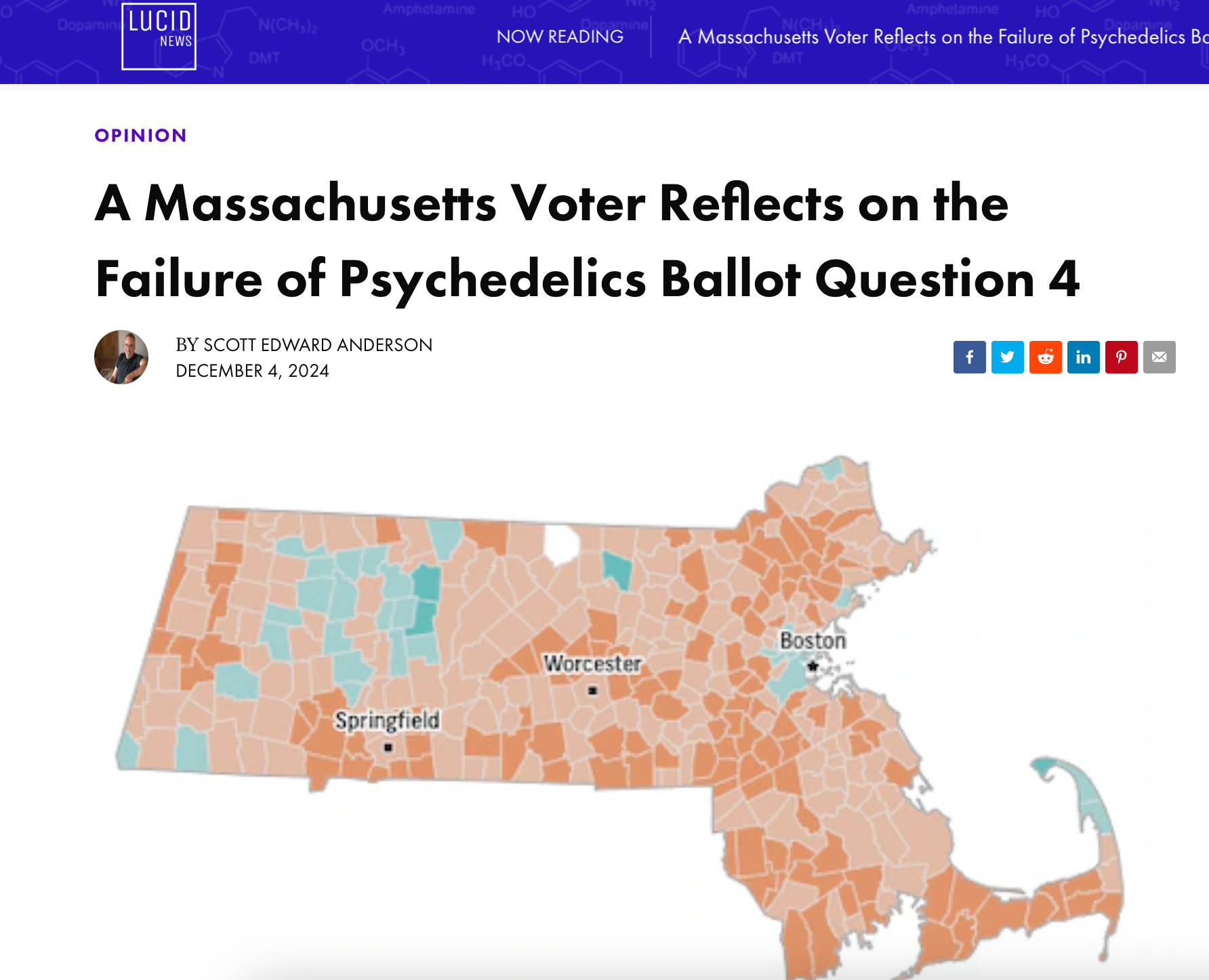

Apparently, they did not.

In this Lucid News op-ed, Massachusetts voter Scott Edward Anderson offers a firsthand account of what might have gone wrong: concerns about safety, ambiguity around regulation, and an overwhelming lack of awareness around the therapeutic potential of psychedelics. Huge shoutout to Scott for taking the time to share his perspective, because it illuminates three key lessons about the intersection of communications and psychedelic policy reform.

Lesson One: If policy is vague, people assume the worst.

One of the loudest concerns Scott heard—especially from opponents like the Coalition for Safe Communities—was about the measure’s home-grow provision. It allowed individuals to cultivate natural psychedelics (like magic mushrooms) in a 12×12-foot space. Critics said this was excessive for personal use and feared it could lead to unregulated sales or teen access.

As someone who isn’t a Massachusetts voter, I went back to my Town Hall notes to see how this was addressed… and it wasn’t.

Slides from Massachusetts’ Vote Yes on 4 Town Hall, Fall 2024

If I had only seen the campaign’s official slides—the ones designed to pass this measure—I wouldn’t know what to say about the 12x12 rule, because it wasn’t mentioned at all. If I’d opened the door just a crack to learn more, now I’m slamming it shut.

Communication isn’t just about social media posts and press releases. It’s written in policy itself. Have you heard the phrase, ‘If you don’t tell your story, someone else will’? This is that—just in a different font.

Lesson Two: Science doesn't actually speak for itself.

The Yes on 4 campaign seemed to believe that the science would speak for itself. But when people associate psychedelics with illicit drug use, a stack of jargon-heavy studies isn’t going to change their minds. What they need is a simple, digestible explanation: How does this work? Why is it safe? Why should I trust it?

When the opposing message (“Teenagers are going to grow psychedelic plants in their bedrooms!”) is loud and clear, your rebuttal must be as well.

Instead of meeting voters where they were, the campaign expected them to do the work. Science isn’t self-explanatory to most people, and they won’t change their minds just because the data exists. You have to translate it into something they actually hear.

Lesson Three: The truth needs better PR.

The failure of Ballot Question 4 wasn’t just about psychedelics. It was about messaging.

What if the campaign had focused on just one substance—say, psilocybin—instead of grouping five together? What if it had led with real stories: veterans, cancer patients, and therapists who’ve seen firsthand what healing looks like? What if it had anticipated fears instead of hoping people would reach the “right” conclusion on their own?

The existence of good information isn’t enough. We need better ways to communicate it. If we want to see progress, we can’t expect people to sift through policy language and research papers on their own. We have to bring the truth to them, in a way that actually lands.

Ballot Question 4 didn’t pass, but the lesson it leaves behind is loud and clear: If we want psychedelic policy reform, we have to use a communications strategy that anticipates opposition, thinks outside of our knowledge confines, and gives the truth a better mic.